More than a million words. That’s how much translation I’ve done in the last six years or so. It has taught me a lot.

When writers give writing advice to aspiring writers, one of the suggestions I’ve encountered more than once is to retype some novels – your favourites as well as some you don’t like – so that you can see what the authors did and learn from it. At the time when I read this advice, I could not imagine doing something so tedious. There was no way I was ever going to do it.

But translating books has forced me to do this – retype existing novels, and render them into another language to boot. I actually engaged with the texts in an even more intense way than simply retyping them. And now that idea of retyping an entire novel doesn’t sound half as dumb as it did at first, I have become one of those writers who recommend this method. Seriously.

Before I get to some of the things I have learned by doing all this translation work, just an overview of the books:

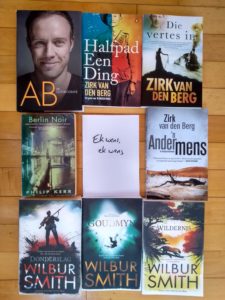

- 3 of my own novels

- a novella I had written

- the autobiography of cricketer AB de Villiers.

- 2 historical crime novels by Philip Kerr

- 3 early historical adventure novels by Wilbur Smith.

I’d like to think my translations have become better over time. After years of minimal practice, Afrikaans has become more readily accessible in my head again, my resources improved, and so did my practical processes.

Technique

I translate in stages. First, I get the text I have to translate into an MS Word document, in a format I like. That also gives me a consistent page count I can use to work out what milestones I have to achieve when to make the deadline. Then I create a separation in the text, usually a row of xxx in highlight.

Then the real work starts, what I consider as Stage 1. Above the bar, I start translating the words below it, rendering the English into Afrikaans as efficiently as I can. I find it easier to work with all the text on one screen. It also makes the project portable and I have even translated while travelling by bus or when waiting to see someone.

As I finish translating a paragraph or group of lines, I delete them. It’s like a worm coming down from above, eating English and excreting Afrikaans. I use some typing shortcuts such as automatic replacements of recurring words that are hard to type, especially the Afrikaans words with diacritical signs on some letters. I also keep notes of issues to take up with the publisher.

That is by far the most time-consuming stage, taking perhaps three-quarters or more of the total project hours.

After this is when the real fun starts, when I put the original text aside, and work fully with the translation. This is where I concentrate on style and idiom. Occasionally I might look at the original if a passage is problematic, but mostly I operate wholly immersed in Afrikaans.

Challenges

While the process is consistent from book to book, each project presents its own challenges.

My own books were the easiest to translate in the sense that I knew what the author meant, and where I didn’t understand the bloody idiot (this happened!), I felt free to change it. Actually, with unpublished books I ended up translating both ways, because when I found something awkward in the original or had an idea that made the translation better, I’d often back-translate that to the original. The biggest challenge was to render the more poetic passages or ones with word-play into the other language. Some thoughts are only striking because of the words with which they can be expressed in a particular language.

The AB de Villiers book threw up two unique challenges: One was procedural – receiving the text piecemeal while working against a tight deadline. The second was cricket terminology. For instance, I had a chart with 40-something fielding positions, and still AB managed to mention a couple of positions not on my chart, or any other I could find. The names of specific cricket shots were equally dumbfounding at times.

And there was also the oddity that I had received originally Afrikaans dialogue from his family life rendered into English, and had to back-translate that. I always wondered how the words have changed in the process.

I am still working on the second of two of British crime novelist Philip Kerr’s Bernie Günther novels. The biggest challenges here are the inconsistent rendering of German (and Russian in the third book) in the originals, and some aspects of Kerr’s style. His characters’ über-cool slang is sometimes impossible to decode. From a writer’s perspective, I found some of his choices between telling and showing a bit mystifying. And he occasionally goes to extraordinary and complicated lengths to make a simple point. When he becomes convoluted, it gets hard to translate.

Actually, here’s a general rule: If the original is written well, it is relatively easy to translate. It is when the original is terrible or brilliant that you struggle to translate it.

Translating Wilbur Smith

I left discussing the Wilbur Smith books for last, because they were by far the most problematic – and instructive.

They were mostly early novels by Smith, and perhaps he had become a better writer over time, but I’ll confess that, unlike Kerr, Smith is not a writer on my reading list and I’ll never find out what his other books are like.

What struck me about those early novels was firstly how badly they have been edited. Some of those books have been in the market constantly for 50 years, and still there were blatant inconsistencies, lapses of logic, etc. In one book, for instance, a character who cannot read, kept cut-outs of newspaper stories. This is unusual enough, but these newspapers were only pubished after the guy’s death! Some of these lapses did provide light relief during the translation.

I also spotted quite a few historical errors, but I suppose before Google those were easier to make.

The narrator sometimes casually makes a sexist or racist statement that was probably unexceptional in the 1960s, but which really grates on the reader now. Together with the publisher, we made the decision to tone down the offending sentiments where possible, though we couldn’t do it to the extent where it would affect events in the story. In Donderslag (The Sound of Thunder) the main character, who recently returned from a safari where he shot 500 (!) elephants, still gives one of his lovers a hiding, for instance.

What I learned

So, what did translating Wilbur Smith teach me?

First, that readers of commercial books like stories, and that little else matters. Smith is good at telling stories, especially at making historical events come to life. Even if, in one case, he carried on for a good hundred pages after the natural end of the story. He also has a knack for honing in on the strongest, most basic human emotions. And he exploits the African milieu well. These are, I believe, the main reasons for his success.

Hopefully some of this has subconsciously rubbed off on me.

I always thought that the aspect of writing that interested me least was plotting, but having read Smith, I am less sure. It is something one can get right as a writer and, when you do, it helps to make the book more attractive for readers. I believe it is possible to marry literary merit with good plotting. To be fair on myself, Half of One Thing was written before I translated Wilbur Smith, and has a smart, tight plot.

Smith’s prose never rises to any heights, but is effective, especially in action sequences. When he goes for lyricism or internal monologue, it tends to bog down. And there are shoddy aspects to his writing, perhaps a factor of working at speed. In one book, almost every brown object is described as “chocolate brown”. I’m fairly confident that in terms of prose, my translation improves on the original. So, in a sense, what I learned in terms of prose was how not to do it.

Perhaps the most important thing I’ve learned from translating the Wilbur Smith books in particular, is to be far more confident in my own writing.